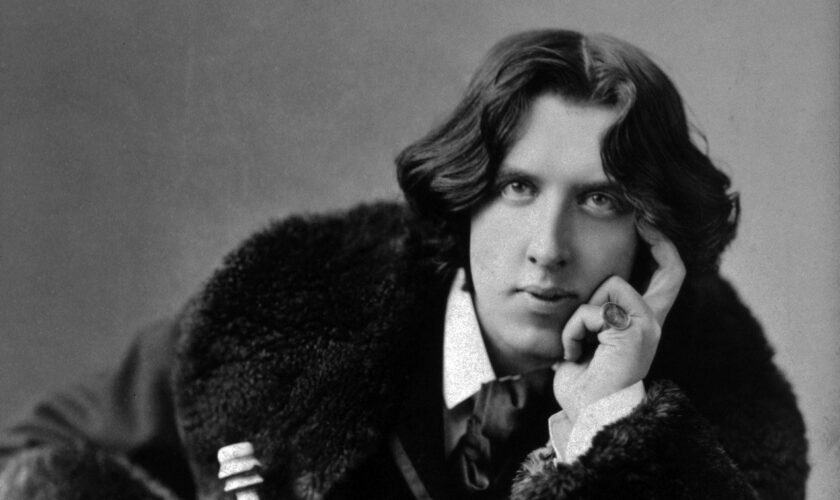

— Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, 1887

When Oscar Wilde wrote these words over 130 years ago, the Western world was in deep mourning.

Not because of any one particular loss, mind you. An overt obsession of many during the Victorian era (1837-1901) was death, dying, and mourning.

In Victorian life, death was everywhere: in the streets, the workplace, peoples’ homes. Families began planning for death long before it actually arrived. Many wedding dowries included women’s handmade funeral shrouds.

Deathcare was provided in the home by family and friends of the deceased. Often, death was the only time a person was photographed.

Attitudes toward death have changed a bit since then.

Today, modern American society tries to bury death. Many go to great lengths to avoid discussing death, or even acknowledging it. As though not talking about it will prevent it from happening.

This attitude extends to our lives. Our elderly are tucked away out of sight and mind in specially designated housing and facilities, instead of revered as wise and valuable contributors to our society . Rather than allowing ourselves to age naturally and gracefully, we are obsessed with looking and acting youthful.

Our loved ones don’t die, and they aren’t dead. Instead they are deceased. They have passed away, passed on, departed, are resting in peace or at eternal rest, are lost; or have succumbed, didn’t make it, or are in a better place. Or (worst of all, in my opinion) they have “lost their battle,” as though life is a war to be won. We devote more time inventing words and phrases that dance around the very idea of death than we do thinking honestly and rationally about our own mortality. No wonder we find it hard to accept that each and every one of us will die someday.

American mainstream culture loves tradition. We have traditional ways to do the important things in life, like being born, getting married, raising a family.

And, of course, dying: typically, one becomes ill, goes to a hospital, and connects to various machines whose function is to keep that person alive until a doctor or family member decides the machines can no longer replace the vital organs and nervous system. The doctor unplugs the machines, the body shuts down and dies, and off it goes to a funeral home for a post-mortem makeover, then laid to rest in a casket that is often expensive.

All behind closed doors, by strangers who perhaps never knew or even saw this person as a living, thriving being. The surviving family receives two final options: burial or cremation.

While many Americans prefer to keep the topic of death six feet under, the “alternative deathcare industry” challenges this status quo. Organizations like The Order of the Good Death, founded by mortician and author Caitlin Doughty (also host of the popular YouTube series “Ask a Mortician”) promote death positivity or the acceptance of death as a natural part of life.

Resources like TalkDeath (talkdeath.com) “encourage positive and constructive conversations around death and dying” and topics ranging from green burial and grief support, to memento mori artwork, to how to host a home funeral.

Death doulas or midwives bridge the gaps among families, medical personnel, and the funeral industry, making death and deathcare personal and family-focused again.

We are no longer forced to make the choice between burial or cremation for our corpses.

We can now also choose among alternative means of body disposition like aquamation, recomposition (aka human composting), and the mushroom death suit (Google it!).

I engage with death on a regular basis, as a death doula, crematory operator, wildlife educator specializing in birds of prey, and unabashed taphophile. Death is as much a part of my life as, well, living.

In this column, we’ll glimpse behind the veil that divides this world from the next, and unearth our own mortality. Let us explore the landscape of death and dying together with honesty, humor, reverence, and love. “You can help me. You can open for me the portals of death’s house, for love is always with you, and love is stronger than death is.” (Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, 1887).