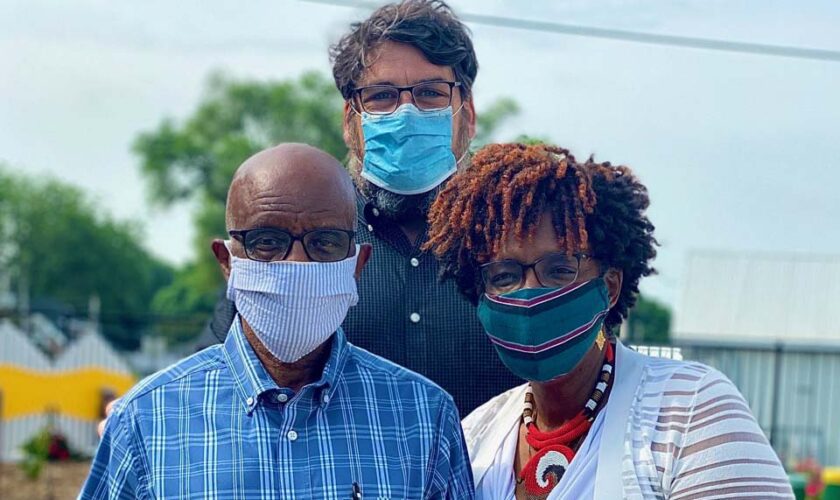

WASHINGTON — Dr. Kesho Scott started bringing George Floyd memorials to her central Iowa hometown of Grinnell, with a small service that ended up attracting about 150 of the town’s 10,000 residents.

A woman from Belle Plaine, a town of 2,500 just west of Cedar Rapids, attended the Grinnell event and asked Scott to come to her town, too. Mingo, a town of 300 near Newton, asked next and ended up drawing about 50 people to a gathering in a resident’s backyard.

Then Marengo, about a half-hour south of Belle Plaine and with about the same population, asked Scott to come, too. Next was nearby Williamsburg, where activist Meredith Hamlyn lived. She had seen Scott speak in Marengo; about 150 of Williamsburg’s 3,000 residents came out for the memorial.

Now, Washington south of Iowa City is the latest small town to host Scott in a memorial and peace proclamation. The event happens from 1:30 to 2:30 p.m. today (Sunday) in Washington’s historic Central Park.

Scott, a retired Grinnell College sociology professor recently honored as a 2020 Woman of Influence by the Business Record in Des Moines, says these small-town Iowa events illustrate that rural Iowa is just as interested in racial justice as big cities.

“What is motivating people to have these peace memorials for the Floyd family, is they want to make it part of their history as a town that they are anti-racist,” she says. “They don’t want the stereotype that comes because they’re living in a predominantly white community.”

The events she’s participating in — organized by Belle Plaine City Administrator Stephen Beck, a former student — are also not “critiques of the police department,” Scott says, although they do raise general questions of inappropriate policing.

“This is memorialship,” Scott says. “This is about what Iowans do well. They show respect for loss. These things are peace memorials. They’re a moment for a community to say ‘we understand.’ “

Scott’s appearance in Washington became reality only after a contentious City Council approval process that included a majority of council members speaking in opposition to the overall Black Lives Matter movement. One council member even called her a “domestic terrorist” while claiming that the issues raised by Floyd’s murder were only relevant to big cities.

It was among the most vivid comments attacking her work in the last two months. Scott has encountered other examples of resistance to her message, including a tractor-riding, flag-waving young man in Williamsburg who tried for an hour to disrupt the event; a man in Marengo who tried to use his revving truck motor to drown out that event; or people bearing fliers opposing the Black Lives Matter movement. Hamlyn said in Williamsburg, a sign about the event was torn, with the word “black” seemingly strategically removed.

But more common, Scott said, is an embracing of her message. Some opponents have even stuck around to peacefully listen. The young man on the tractor, for example, left and respected the group’s right to gather and converse after some attendees helped him see that doing so would be the better way to respect the American flag.

And even though four of Washington’s six City Council members said they “opposed Black Lives Matter,” four of the six also voted in support of the event itself and also spoke out in support of Scott speaking.

Scott and Beck are also talking with Tama, Mount Pleasant, Mount Vernon, Wilton and Vinton. Eventually, they hope to expand to western Iowa.

“i want to see our communities become more inclusive, anti-racist places where people feel safe to work, go to school, grow and contribute to each community in their own way,” says Beck, who is the city administrator for Belle Plaine and also a School Board member and former City Council member there. “I want people of color to feel welcome, and that will help everybody in the community, because they will have a more whole lifestyle and education.”

Scott said she was especially touched by learning that Marengo’s residents said “no” decades ago to a movement for its tiny Andrew Carnegie Library to prohibit Blacks, a condition that was common in many of the libraries the early 1900s philanthropist had funded throughout the country.

And she often reminds the people at her events that the Midwest has a long tradition of prejudice based on religion, reminding them of a time when Catholics rather than people of color were the “outsiders” who experienced prejudice and discrimination.

“At the turn of the century, most small-town minorities were people who were Catholic. They got treated like crap in places like iowa, in small towns. People who were Catholic were seen as aligned with the Pope, and those communities were Protestant.”

Also among Scott’s key messages at these events is shared pain. She taps into a sense of compassion and grief over loss, Hamlyn says, and then builds on that shared compassion to press for justice.

“There’s a heavy emphasis on making it a memorial to those we’ve lost already,” Hamlyn says. “Humanizing those moments and feeling sad about it is powerful in moving people to get involved and become part of the solution.”

Scott also drives home that people of color, and rural Iowans, share many of the same concerns and fears.

Lack of resources and poverty are two, she says. Scott points out that 11 to 14 percent of Iowans are considered below the poverty line, meaning they earn $12,760 or less as a single person, or $26,200 or less as a family of four. Like many inner-city residents and people of color, rural Iowans also share the problem of limited access to health care, Scott says.

She considers her work touring small-town Iowa to be a form of support for people who are trying to make a difference.

“I watched as a kid during the civil rights movement, and saw white people in the civil rights movement who were allies to ending racial segregation in the United States,” says Scott, who grew up in Detroit. “I’m now an ally to white communities that are saying, ‘These issues are in our town too. Poverty is in our town too. Lack of resources are in our town too. Hatred of gay people is in our town, too. We want to say something about that.’

“I’m being an ally to them. I’m grateful to be an ally to them. We can support each other.”

Hamlyn, who has lived in Williamsburg for almost nine years, says the demographics of so many Iowa small towns are predominantly white, which means their residents hardly ever even see people of color.

“The people we surround ourself with is one way we can become more empathetic to the struggles of people that are different than us,” she says. “It’s important as a white person who has understood what discrimination can be like to use my whiteness to bring the conversation out and say, ‘Look, we’re gonna talk about this.’

“I don’t think people are intentionally evil, but white privilege is something that a lot of people have benefited from. And unless you’re aware of it, you can kind of truck along in life and be completely oblivious to the issues of people who don’t look like you or are a different race than you.”

Hamlyn also said that focusing on a “peace proclamation” and a “memorial” are effective ways to reach out to small-town Iowans who may be “disconnected” because they never have the opportunity to interact with people of color.

“It’s important for more people to be bold,” she says,” but it’s actually more important to make the people who are here feel welcome and to learn, so that when we go to other places, we can help them learn as well.”

Another quality that Scott carries to her small-town gatherings is her deep love for Iowa. She is the first African-American woman to earn a doctorate from the University of Iowa with a degree in American studies, and the first-ever African-American woman to receive tenure at Grinnell College, where she taught for three decades.

Scott was also honored by the Iowa Legislature last February for her contributions to diversity throughout her career.

“This state of Iowa invested in that Ph.D. I earned. I was invited to come study here, and I decided to stay,” she says. “This is my home. I’m going to be buried in the cemetery in my town. I’m not coming from somewhere else.

“I teach their children. I’m not an outside agitator i live at mile marker 186. I’m a neighbor who lives down the street,” she says. “People are inviting me to their own towns. It’s the people that are doing this.”

(Top photo provided by Grinnell College)