ROCK ISLAND, IL. — The story that will be told at 6 p.m. tonight at the Rock Island Public Library-Watts-Midtown Branch takes place hundreds of miles from Illinois and Iowa, deep in the swampland of southern Georgia. It’s about land that is hardly inhabited today except by wood storks and hundreds of other bird species.

But for Gaye Shannon Burnett, head of the Azubuike AFrican American Council of the Arts that is presenting the documentary film, “The Taking of Harris Neck is a “call for justice” for all Black people “and the broader Quad Cities community.”

“It’s a mirror reflecting our strength and resilience,” she said. “Seeing the resilience of formerly enslaved Black people who faced deliberate theft of their land ownership inspires us to tackle current challenges.”

Gaye Shannon Burnett, founder of the Azubuike Council of African American Arts, organized tonight’s showing of “The Taking of Harris Neck.”

“The Taking of Harris Neck” shows how more than 2,600 acres were seized in 1942 from a community of Black residents in Harris Neck, by an almost exclusively white local and federal government. The move, justified at the time by wartime needs for an airfield there, destroyed what used to be a thriving Gullah community that “lived off the land.” Most of its residents were descendants of slaves, freed through emancipation who had lived and worked there when it was a plantation. Many were also originally from the Sierra Leone region of Africa that would become known as Gullah Geechee,

The seizure also violated laws of eminent domain and treated the few white residents and landowners of Harris Neck more profitably than its Black residents.

Since 1962, Harris Neck has been a wildlife refuge owned by the federal Department of the Interior. But while one group of descendants has signed a memo of agreement with the federal government to keep the refuge, another group is asking that 500 acres of the original Harris Neck be turned over for conversion to ‘a museum and tribute to the original Gullah community.

Government’s Harris Neck seizure in 1942 devastated thriving Gullah community

Those two groups may differ on what should happen to the land now, but they agree on the wrongs committed in the past by the federal government, and the devastation those wrongs wreaked on the Native American and Black Gullah community that lived there for decades.

“This was a conspiracy” involving the federal government, the local government, and “a handful of white families including a very infamous sheriff who ran the county with an iron hand,” says David Kelly, head of the Harris Neck Land Trust that is seeking the 500 acres. Those powerful local families hoped the Harris Neck land would become theirs after the temporary airfield was no longer needed, Kelly says.

David Kelly and other members of the Harris Neck Land Trust end a recent meeting with a prayer circle.

A devastating account of the take-over can be found on the website of the Fish and Wildlife Service that is now responsible for the land.

“The airfield’s construction destroyed much of the original Harris Neck Gullah community.” writes the FWS. “Some displaced residents purchased land nearby, believing verbal assurances that their land would be returned. Many others had to relocate.” Despite promises the land would be returned ot the original owners, the McIngosh County’s power-brokers got their wish, Kelly said, and the land was turned over to the government.

Another group, the Direct Descendants of Harris Neck Community, reached an agreement in 2020 with the federal government to help preserve the wildlife refuge. However the land ends up being used, Burnett says Harris Neck “is more than history.”

“It connects us to a shared past of overcoming adversity, showing how past struggles shape today and tomorrow.”

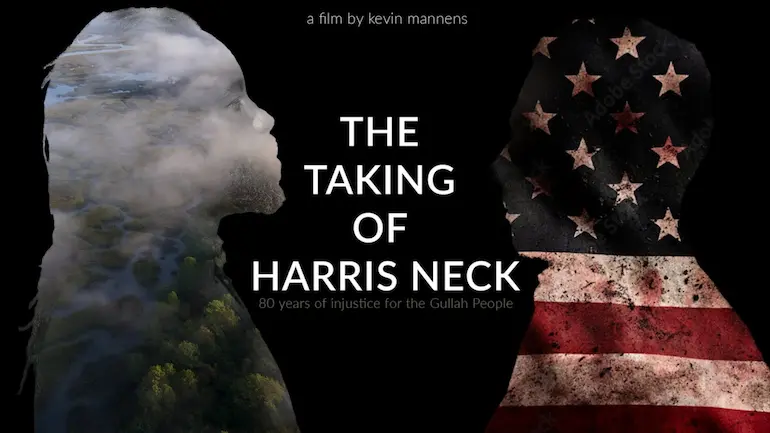

The documentary is produced by Kevin Mannens, a New Mexico State University professor who is also an Academy Award-winning visual effects designer. The film was shown at the Rock Island Public Library Watts-Midtown Branch and is also viewable on YouTube.