There’s a common scene Chris Whitmore encounters as animal control coordinator for Iowa City.

A family, often from a rural homestead or tiny town, brings in a six-week-old kitten to the shelter for adoption. “Where’s the mother?” Whitmore or her staff will ask.

“We don’t know where she went,” they’ll answer. “Well, would you like to try to live-trap her so she can be spayed?” they’re asked. “No, not really,” is usually their answer.

“And they just keep the cycle going of bringing kittens in to us year after year,” Whitmore says. “We also often have farmers or rural people who will bring in kittens that are eight months old. By that time, they don’t make good pets, no one’s handled them. They’re like feral cats, but not.

“And they won’t ever bring the mother in. It’s just the same cycle over and over again.”

The cycle keeps public and private shelters overflowing with kittens that are often hard or impossible to adopt out because they are so unaccustomed to human contact. The vast majority of feral cats are euthanized after a brief stay in the public shelter.

It’s one of the cycles that taxes the resources and time of shelters. It also leads to thousands of healthy but unadoptable kittens being euthanized every year, after miserable final days contained indoors in an environment they find terrifying.

Whitmore is hoping the old-time approach to “barn cats,” “farm cats,” “community cats” and feral cats will start to change now that Iowa City has a TNR (trap-neuter-return) ordinance. The new law makes it legal to not only feed cats that don’t have traditional indoor “homes,” but also to live-trap them humanely for the purposes of spaying and neutering.

Iowa City’s new law, passed last spring and put into action in October, is the latest in a swirl of TNR efforts that have been sweeping across Iowa in the past two years. It’s a change from the outdated attitude many have toward feral cats, which is to regard them as either pests, or as self-sufficient predators to be exploited for controlling barn and farmyard rodent populations.

TNR allows people to care for cats without homes in a way that also helps stem their population growth humanely, relieving a huge burden on shelter resources and making life better for the cats themselves, research shows.

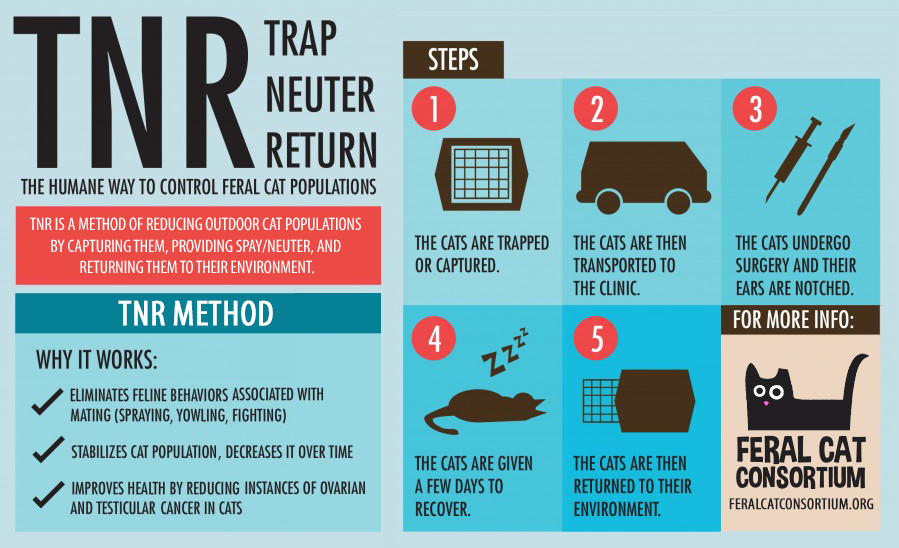

It involves using humane drop or box traps to capture unaltered male and female cats, transporting them to an agency or shelter that provides spay/neuter surgeries, returning them to where they were captured for release, then providing them food, water and basic veterinary care for the rest of their lives.

This process leads, over several years, to fewer unowned cats. It also means fewer male cats fighting in the wild, and fewer unowned cats scrounging for food, living miserable lives, and dying miserable deaths.

Des Moines also enacted a new TNR program last year; coordinator Megan Weidmann says demand has already exceeded anticipation, with 600 surgeries performed since May 2019. The program had expected 500 surgeries.

“To have a TNR ordinance and enforce it makes a huge difference,” Weidmann says. “ ‘Catch and kill’ doesn’t do any good. And just catching doesn’t do any good. If these outside cats are brought into the shelter, their well-being is comprised, which in turns compromises healthy and friendly cats that can be adopted. There is so much energy and time spent on every cat. If we can get these community cats brought in for surgery, and returned, that opens up the availability for us to serve people in crisis.”

The challenge is educating and engaging the public in the process of TNR. Whitmore handled most of the estimated 15 TNR cases that Iowa City undertook before the cold set in; she hopes education programs will engage more of the public to participate in the humane trapping and return process.

“A lot of people are not really sure how it’s going to help them with their cat population issue,” she says. “We try to explain to them about the funnel effect, why this will actually help keep your population down. Why it’s really a win-win.”

TNR also helps shelters devote less resources, time and money to killing cats. Whitmore said Iowa City’s euthanasia rate has sat at 15 to 18 percent for the last three years; the new TNR program will ideally help lower that.

For a shelter to be considered “no-kill,” a standard 90 percent “live release” rate is the goal; this accounts for 10 percent of shelter animals deemed too ill for a quality of life, and for whom euthanasia is humane,” says Best Friends Animal Society.

Throughout Iowa, several communities are enacting new TNR programs:

- The Iowa Humane Alliance program through Cedar Rapids, which serves much of central and eastern Iowa, has completed 33,000 surgeries since 2013 and is aiming to expand.

- Marshalltown started a TNR program in May.

- Jefferson in Greene County enacted a successful TNR program, considered among the state’s leaders in TNR after a horrendous incident of mass cat-killing by bullets attracted national attention.

- Boone Area Humane Society and areas around Ames enacted a TNR program in 2017 and its shelter has a save rate of 95 to 98 percent.

- Winterset began a TNR program in 2017 and has virtually eliminated complaints about stray cats, says Alley Cat Allies.

- The Harrison County Humane Society runs a thriving TNR program.

Whitmore says she hopes Coralville will also pass a TNR ordinance soon.